In “Crossroads,” bad decisions and bad faith weigh down the characters—and propel the novel to startling heights.

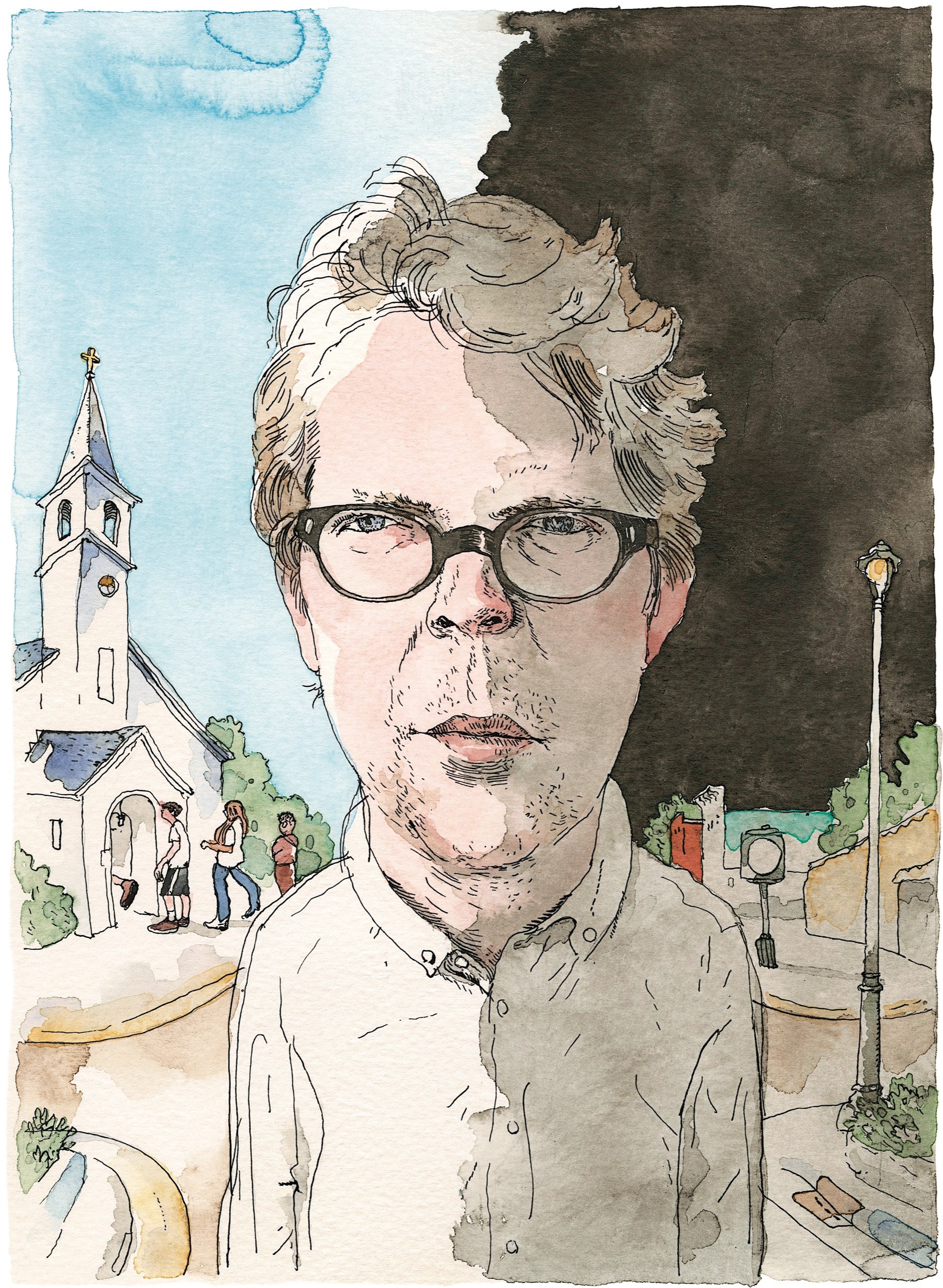

A rabbi, a preacher, and a drug dealer walk into a Christmas party. This is not the setup to a joke; it is the setup to a pivotal scene in “Crossroads,” Jonathan Franzen’s new novel. The drug dealer is Perry, the fifteen-year-old son of Russ Hildebrandt, the associate pastor of the First Reformed Church of New Prospect, Illinois. That makes him a P.K., or preacher’s kid, a famously fraught identity that some people navigate by striving to be good enough to live up to the accompanying expectations, and others by becoming conspicuously, defiantly bad. When we first meet Perry, he is stranded between the two options: brilliant but troubled, he has lately resolved to quit doing drugs, be nicer to his sister, and generally become a better person, but he is finding the whole idea of goodness difficult to comprehend.

At the party—an annual interfaith affair for the religious leaders of New Prospect—he convinces himself, through a brief bargaining session with his better angels, that drinking is not technically a contravention of his resolution, then covertly helps himself to a generous amount of gløgg, the potent Scandinavian drink on offer. While the booze works its way into his system, he strikes up a conversation with a rabbi and a pastor about a question that is much on his mind: whether an action can be considered good if the actor knows that by taking it he will gain either pleasure or advantage. Is a godly man truly good if “he enjoys the feeling of being righteous, or he wants eternal life”? Is Perry himself good if he can’t stop his busy mind from tallying up the ancillary benefits of doing the right thing? The rabbi and the pastor are pleasantly surprised that a teen-ager is interested in such morally substantive matters, but the hostess, familiar with Perry and therefore suspicious of him, tries to steer him away from the clergy. Perry, blood alcohol surging, promptly explodes; as the party falls silent, his mother steps into the room. “This is what I’m talking about,” he exclaims. “No matter what I do, it’s always me who’s in the wrong.” Drunk, desperate, ashamed, he bursts into tears, and into the only apologia available to him: “I’m doing the best I can!”